Published: 16 Jan 2013 at 23.45

One month after a prominent activist mysteriously vanished, Laos’ nascent civil society is living in fear despite the communist regime’s vow it had nothing to do with his disappearance.

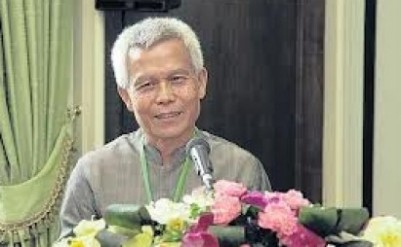

This handout picture received on January 15, 2013, provided by the Somphone family and taken in 2005, shows Sombath Somphone of Laos at an unknown location in the Philippines.

Sombath Somphone, 62, the founder of a non-governmental organisation campaigning for sustainable development, went missing in Vientiane while driving home on December 15.

Images from CCTV cameras, obtained by Sombath’s family and published online, show him being taken away from a police post by two unidentified individuals. He has not been seen since.

The secretive communist regime, which has ruled Laos with an iron fist since 1975, has for the last few years appeared to be gradually opening up, allowing local civil society groups to flourish.

But Sombath’s disappearance has sent jitters through the activist network.

It came just a few weeks after Laos expelled Anne-Sophie Gindroz, the outspoken country director of Swiss charity Helvetas, for criticising the communist government that is led by President Choummaly Sayasone.

“Other civil society leaders are extremely worried, some have — I hope temporarily — left the country. It could well be a big step back,” said one development professional who has known Sombath for 20 years and requested anonymity.

Sombath, whose work for the Participatory Development Training Centre (PADETC) targeted the country’s marginalised and impoverished rural population, had played a key part in the apparent emergence of Laos’ long-muzzled civil society movement.

Hopes had been raised “of a process that was going to result in the Lao government recognising that NGOs have a role in a modern society”, said Phil Robertson of New York-based Human Rights Watch.

But those hopes had “probably been set back now in a significant way by Sombath’s disappearance,” he said, adding there was a “growing fear within civil society groups in Laos”.

Laos-based activists contacted by AFP spoke only on condition of anonymity, reflecting concern for their safety.

But the regime promises Sombath is not in their hands.

“The concerned authority is accelerating the investigations, collecting evidence in order to reach a conclusion,” Yong Chanthalangsy, Laos’ Ambassador at the United Nations in Geneva said.

“It may be possible Mr Sombath has been kidnapped perhaps because of a personal conflict or a conflict in business or some other reasons,” he added in a letter published in the Vientiane Times on January 4.

But local NGOs and the international community are unconvinced by the explanation.

“The story doesn’t add up,” said Charles Santiago, a Malaysian member of parliament who this week led a delegation of parliamentarians from Southeast Asia to Vientiane to pressure the authorities into action.

“The government simply cannot say after one month that they still can’t trace him. This stone-walling is not acceptable,” he said, noting that Sombath vanished “in a police environment” and there has been no demand for ransom.

At a press conference in Bangkok following the visit to Laos, Santiago said Wednesday that “the government has no political will to resolve the problem.”

However, many observers are struggling to understand why the regime, which has sought over the last few years to shed its image as one of the world’s most reclusive countries, would have decided to detain Sombath in secret.

The move could have been triggered by the participation of many local activists, including Sombath, in the Asia Europe People’s Forum (AEPF) last October, says Santiago who is the Forum’s Asian coordinator.

“AEPF must have triggered some anxiety within the politburo, because some of the people who came talked about land grabs and so on and so forth, so they want to send a message that this is not acceptable,” Santiago said, noting that the meeting was held just before a major Asia-Europe (Asem) summit.

In a country where major infrastructure projects are displacing tens of thousands of people, “it is also possible companies involved in land grabs are using members of the various groups within the party to send a message” he said.

Other analysts point to the diverging currents at the heart of the regime.

“It may be that behind this is a conflict between the old guard and those who are pushing to move closer to the international community,” one foreign observer said, noting that Laos was set to join the World Trade Organisation in February.

Meanwhile, Sombath’s family is struggling to keep a low profile.

“I have at no point refuted the government’s statement,” said Ng Shui Meng, in an open letter published online, calling on the government to find her husband.

“Sombath has a medical condition that needs daily medication and once returned to me, I would take Sombath to seek medical attention abroad until his full recuperation,” she said.

Phil Robertson

Deputy Director, Asia Division

Thai mobile: +66-85-060-8406

US mobile: +1-917-378-4097

Email: RobertP@hrw.org

Skype: philrobertsonjr

Twitter: @Reaproy

Human Rights Watch (HRW)

350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor

New York, NY 10118-3299

Leave a comment